Most people don’t create language on purpose. We learn it, from our parents, our peers, nowadays from the internet. In addition, when we use language, whether spoken or in writing, we don’t consciously distribute words according to some statistical model. So why do natural languages such as English follow a power law distribution so closely?

Zipf’s Law is a model used to describe empirical data that states that the number of the occurrences of an event is inversely proportional to its popularity. That is, if an element’s frequency has frequency rank r, we have some constant factor C and exponent alpha such that

If we arrange English words found in texts by order of their popularity, for example, at the beginning of the list, we get the, be, a, and, of, etc, these words will closely follow this distribution. According to Li, we have C approximately 0.1 and alpha approximately 1. That is, the most common word occurs 1/10th of the time, the next most common word occurs 1/20th of the time, etc. This is follow more closely by more common words since they are guaranteed to be more frequent. While we would expect some distribution where where the words with the highest frequency rank have the most occurrences, why this would follow a power law is not obvious.

Zipf proposed that humans follow the principle of least effort, that is, speakers of a language will put in only as much work as necessary to convey intention through talking. This isn’t done on purpose, but as a result, there is an equal distribution of effort where more general words are used much more often. However, this doesn’t completely explain the phenomenon.

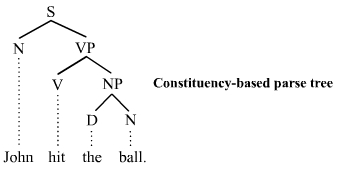

We can consider the network structure of this problem. Like many human processes, language can be modeled using graphs. In particular, parse trees can describe not only the structure of sentences, but how humans think about creating those sentences. Again, while not deliberately done by people, people structure their thinking in terms of phrases such as noun phrases, verb phrases, etc. The most common words are used throughout these different types of phrases. Thus, we can expect to see frequency rank and number of occurrences follow some sort of log-log structure, such as in Zipf’s law and therefore a power law distribution.

References

Adamic, Lada A. “Zipf, Power-Laws, and Pareto – a Ranking Tutorial.” Zipf, Power-Law, Pareto – a Ranking Tutorial, Information Dynamics Lab, HP Labs, www.hpl.hp.com/research/idl/papers/ranking/ranking.html.

Li, W. “Random Texts Exhibit Zipf’s-Law-like Word Frequency Distribution.” IEEE Transactions on Information Theory, vol. 38, no. 6, 1992, pp. 1842–1845., doi:10.1109/18.165464.

Wyllys , Ronald E. “Empirical and Theoretical Bases of Zipf’s Law .” Library Trends, 1981, pp. 53–64., doi:10.1.1.562.5217.

Zipf, Human Behavior and the Principle of Least Effort

It kinda makes sense how people learning English can follow a power-law distribution. While I also think people usually learn their first language as a baby through nurturing, I also know that many people have English as their second language. This is since English is so widely known to many cultures around the world, where if people want to do business or communicate with others around the world, then they also have to learn English. This, in turn, makes English also more popular, which is also a sort of richer-get-richer process that just gets bigger and bigger as time goes on.