For the past few years, NBA teams have been relying more on statistics and mathematics to scout draft picks, game plan for certain opponents, and decide how they wanna space the floor. In this article I found one application of game theory, which analyses how NBA teams decide to guard prolific three point shooters. The article focuses specifically on Steph Curry and James Harden, two of the greatest three point shooters in today’s game.

The authors of the article boil a possesion down to two players: The defending team and the attacker. Each player has three strategies: The defenders can either choose to send a player to press the attacker from half court, stick to a more traditional defense around the 3-point arc, or pack the paint with players.

On offense, the attacker can either choose to take a deep 3 (The authors gave no formal definition of a deep 3 here, but according to espn.com, a deep three can be a shot that occurs more than 3 feet away from the 3 point line), take a regular 3 pointer, or drive to the rim. The authors define payoff as a function of each player’s efficiency (Points per attempt) as a result of each person’s strategy.

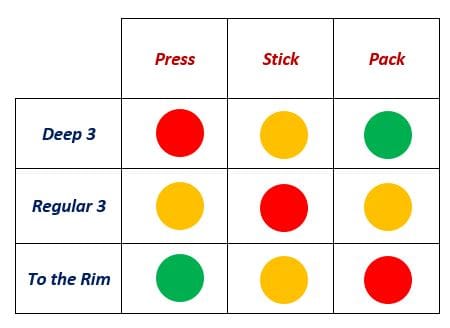

Firstly, the authors create a generalized payoff matrix, that looks like this:

This is not for a particular player, and doesn’t show efficiency values, but its helpful to get an intuition for the general efficiency of each strategy. Intuitively, packing the paint counters a drive, sticking to a traditional offense counters the normal 3, and pressuring the defender from half-court counters a deep 3. Basically, the further away the attacker is from the defending team, the more likely they are to score points. The general matrix is nice, but we can actually look at the matrices for specific players and come up with some very interesting conclusions:

In class we talked about dominant strategies (There is no dominant strategy in the above matricies, by the way), but the authors here actually introduce something we haven’t talked about yet, a dominated strategy:

“A strategy is dominated if, regardless of what any other players do, the strategy earns a smaller payoff than some other strategy. Hence, a strategy is dominated if it is always better to play some other strategy, regardless of what opponents may do.”

Surprisingly, there actually is a dominated strategy in our matrices. Regardless of what the defenders choose to do, taking a regular 3 is never the best option. If the defenders press the attacker or stick players around the arc, it’s optimal to drive to the rim, and if they pack the paint, its optimal to take a deep 3.

The last thing I want to note (as an aside) is Curry’s bonkers efficiency on deep 3’s, especially while contested: 0.93/3 is the calculation (Points per attempt/number of points) works out to 31%. This article was written in 2018, and at the time, the league average from 3 was 35%. That means that curry shoots contested 3-pointers from way beyond the 3-point line almost as efficiently as the rest of the league shoots regular 3 pointers! I guess that’s why there are so many clips of him doing stuff like this:

Works Cited (Main Article, Definitions, statistics):

Natarajan, S. (2018, July 31). Nylon Calculus: Game theory and the deep 3. Retrieved November 06, 2020, from https://fansided.com/2018/07/31/nylon-calculus-game-theory-deep-3/

Goldsberry, K. (2019, December 17). How deep, audacious 3-pointers are taking over the NBA. Retrieved November 06, 2020, from https://www.espn.com/nba/story/_/id/28312678/how-deep-audacious-3-pointers-taking-nba