We all made friends throughout our lives, some made more friends, some made less. But do you know that you actually have less friends than you thought you had? Now to illustrate this, think about the friends you have on social media, whether its Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Wechat, most likely you will realize that you have connections to more people than you actually talk to and consider as friends.

This is based off of the friendship paradox, a form of sampling bias which states friends of a person tends to have more friends than the person thinks. This observation was first talked about in 1991, where a sociologist Scott Feld, conducted a study on social networks of people. His study was to take a deep dive into the average number of friends a person has in their own network and compared it with the average number of friends this person’s friends have. He concluded that the average number of person’s friends is always higher than the average number of friends for this person.

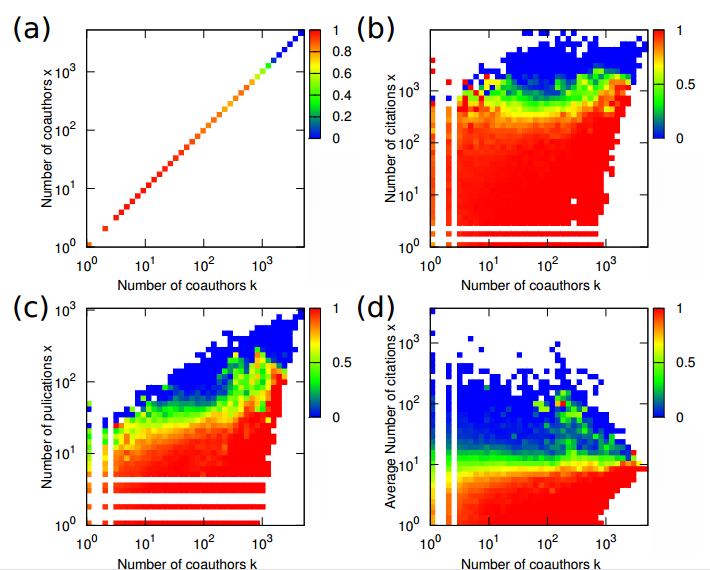

Another example conducted by Young-Ho Eom and Hang-Hyun Jo at Aalto, in which one study they conducted was taking two academic networks, where scientists are linked if they have co-authored papers together. A graph was generated where each node is a scientist and was represented in a paradox holding probability they defined as h (k, x) where k is the degree and x is the node characteristics.

Graph a is a representation of numbers of coauthors, graph b is for the number of citations, graph c is the number of publications and graph d is the average number of citations per publications.

Later on in the study, they conducted using different sampling strategies to see if other sampling methods yield the similar results. Here are the characteristic distributions of the sampled data in the network using different sampling methods.

The common observations from the graphs, which are degree distributions, is that the denser the distributions, the better sampling it implies for the high characteristic nodes. Also, in most cases, the friend sampling shows a better result than random sampling, but one area, which is the average number of citations per publications in the network. As we can see in graph D, that the degree characteristic correlation is very small, around 0.07, but still yields very good results in comparison to other methods.

As expected, looking at a specific scientist and compare it to its co-authors, it reflects the results of the friendship paradox, where the co-authors have more co-authors than the selected scientist. The reason behind this paradox is because of how the graphs are constructed and how the ties between nodes structured.

Do not feel inadequate about “having less friends than your friends”, since most people are actually in similar positions. Just remember friends are all about the quality not the quantity.

Sources:

ArXiv, E. (2020, April 02). How the Friendship Paradox Makes Your Friends Better Than You Are. Retrieved October 17, 2020, from https://www.technologyreview.com/2014/01/14/174587/how-the-friendship-paradox-makes-your-friends-better-than-you-are/

Eom, Y., & Jo, H. (2014, April 10). Generalized friendship paradox in complex networks: The case of scientific collaboration. Retrieved October 17, 2020, from https://arxiv.org/abs/1401.1458